Joseph/Ephraim/Gideon/James/Eunice Hawley

At War With the Shakers

By MARY BETH NORTON

Published: September 17, 2010

Modern Americans, bombarded with stories of celebrity divorces, probably assume that the tabloid breakup is a recent phenomenon. This lively, well-written and engrossing tale proves them wrong. Even before tabloids existed, a juicy 1810s scandal caused by an erring husband — or was it rather his wife? — attracted widespread public attention.

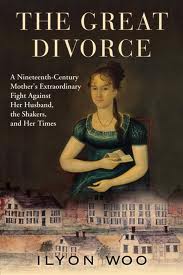

THE GREAT DIVORCE

A Nineteenth-Century Mother’s Extraordinary Fight Against Her Husband, the Shakers, and Her Times

By Ilyon Woo

The Great Divorce by Ilyon Woo

404 pp. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Excerpt: ‘The Great Divorce’ (Google Books)

The combat described in “The Great Divorce” was three-cornered. On one side: Eunice Chapman of Durham, N.Y., mother of three young children, unhappily married to a feckless man who drank to excess and seemed unable to run a successful business. On another: her husband, James, who found that joining the celibate, communal Shaker religious sect gave him the structure he needed to live soberly and productively. And on the third: the Shakers themselves, concerned with thwarting Eunice’s unremitting attacks on their organization.

Ilyon Woo has ably pieced together the story of this triangular struggle. She places the Chapmans’ battle in the context of similar contests: theirs was not the only family torn apart by one partner’s decision to join the Shakers. The sect insisted that wives could not join unless husbands also did. Initially, such a rule did not apply when spousal roles were reversed, but the Shakers’ experience with the resolute Eunice Chapman led them to make it universal.

The Chapmans, along with many contemporaries, were deeply religious and open to new spiritual ideas. When James felt drawn to the Shakers, Eunice reluctantly agreed to join him at a settlement in Watervliet, near Albany, for a brief trial period. But once there she became bitterly unhappy and resisted many of the Shakers’ practices, along with their religious teachings. Soon, she returned home to her children. Under prevailing law, though, James had sole legal control, and he secretly carried them to Watervliet. Later, he and the Shakers moved them to a settlement at Enfield, N.H.

And so began the contest that occupies most of this book. Eunice, determined to retrieve her children and regain legal independence, appealed to the New York Legislature for a divorce. She published pamphlets vividly portraying herself as a victimized wife, helpless to prevent the fanatical Shakers from holding her children captive against their will. James, by contrast, insisted that the Shakers had rescued the children from an impoverished, shrewish single parent. The Shakers, fully complicit in keeping the children out of Eunice’s hands, disingenuously declared ignorance of their whereabouts and claimed to be unable to control James’s actions. Both they and their allies in the Legislature cast Eunice in the role of a “disorderly” woman. What, after all, was the subtext of her struggle against the upstanding, celibate Shakers? It must be that unmentionable characteristic for a virtuous woman of the day: sexual desire.

But Eunice won the five-year battle of competing narratives. The image of the victimized wife triumphed over sexualized innuendo. In 1818, Eunice gained her legislative divorce — the only one ever granted in New York. She also regained her children, primarily by raising a mob that threatened to attack the Enfield Shaker village. The youngsters at first wanted to stay at Enfield, yet none ever lived in a Shaker settlement again.

Although Woo first encountered the Chapmans while researching her Columbia doctoral dissertation, “The Great Divorce” is inadequately annotated for a work of history. The sketchy endnotes are difficult to relate to the book’s text, and sometimes fail to indicate clearly the page of the document to which they refer. What’s more, Woo provides neither index nor formal bibliography. To anyone hoping to track her sources, she says, in effect: trust me. That will do for some readers, but surely not for all.

A version of this review appeared in print on September 19, 2010, on page BR20 of the Sunday Book Review, The New York Times.